Mars has long been a favorite target for space-probe programs. The first to visit was Mariner 4 in 1965. Its successor, Mariner 9, fundamentally changed the way we humans thought of Mars. Viking 1 and 2 landed on Mars in 1976 and searched—inconclusively—for signs of life at their landing sites.

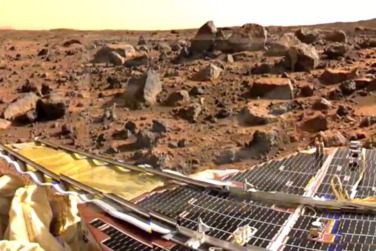

The Pathfinder mission in 1997 proved it was possible to bounce down to a landing using a combination of aero-braking, parachutes, retro-rockets, and airbags. And that once down on the surface, it was practical to dispatch small, solar-powered rovers to do useful science on Mars.

There was a lot riding on the Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs) of 2003-2004. Several failures of prior missions had set the stage, and the MERs themselves were breaking new technological and scientific ground, but both landed safely and began beaming back stunning color images of the planet's surface. Even more spectacular was the conclusive discovery that parts of Mars had been covered by shallow water lakes or seas for a significant length of time; the planet could have once supported life.

It seems that human science has now renewed its commitment to trying to comprehend Mars. A large number of robotic missions are planned for the fourth planet, some of them bound to return samples of rock, dust, and possibly ice.

And where robots go, perhaps people will follow.